Noted economist and Nobel laureate Robert Lucas Jr died on Monday. Lucas was one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, and his work was felt broadly across a number of fields. He did far too much to be easily characterized, but if one were to try, I think it would be fair he was the chap who objected when someone else said “let’s just hold this constant and …”. It’s nice to have simple model, but it’s better to have a useful model.

For us in the field of decision and risk analysis, the most memorable of Lucas’ contributions might be the famous Lucas Critique. As he put it in a blockbuster 1976 paper:

Given that the structure of an econometric model consists of optimal decision rules of economic agents, and that optimal decision rules vary systematically with changes in the structure of series relevant to the decision maker, it follows that any change in policy will systematically alter the structure of econometric models.

At the time, Lucas was mainly interested in macroeconomic variables – what happens when government policy makers turn the knobs to try to reduce inflation and unemployment – but the principle is far more general. If you build and train a model that explains observations under one set of rules, and then you change the rules, the parameters in your model are probably wrong (even the structure of your model might be wrong).

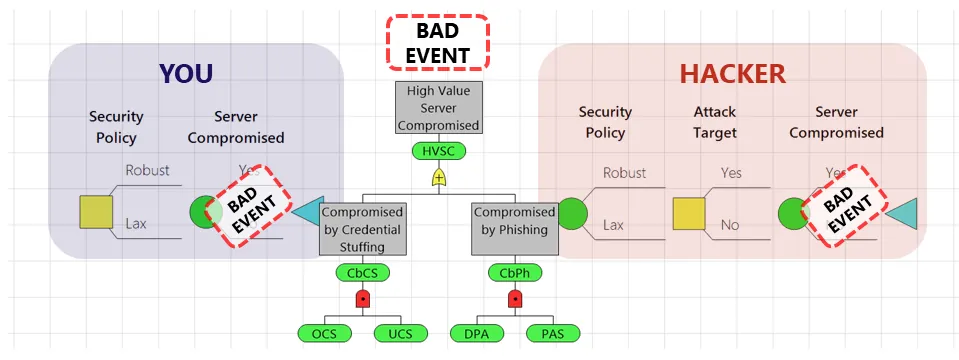

To see this, let’s take an example from cybersecurity. What’s the probability that an adversary will successfully employ a credential stuffing attack against a certain high value edge server with username/password authentication?

Of course it depends on the particulars. Maybe the server has a stringent password complexity policy and locks users out after three failed attempts, so it’s quite low. What if that’s a UX nightmare and we’re considering relaxing the policy? Perhaps nobody has ever executed a successful credential stuffing attack against us, and our fancy log analyzer says nobody has ever even tried. So it’s OK, right?

That’s where those agents and decision rules come in. Maybe the bad guys trying to penetrate your system have never tried because the stringent policy makes an attack unlikely to succeed. If you change the rules, the optimal decisions for the bad guys also change. Maybe they’re presently trying to craft a double bankshot pfishing attack, but if credential stuffing suddenly looks easier, they’ll redirect their efforts to the point of greater vulnerability. The header image above depicts this cyber security example.

When can you hold some parameters constant? When they’re fundamental values of the participants. Your adversaries place some value on the data they’d like to steal from you; that doesn’t change when you alter your defenses.

So, remember Robert Lucas for his many contributions to human knowledge, but in particular be humble about your use of data from an old regime in your assessments of risk.