{width=“50%”

height=“50%”}

{width=“50%”

height=“50%”}

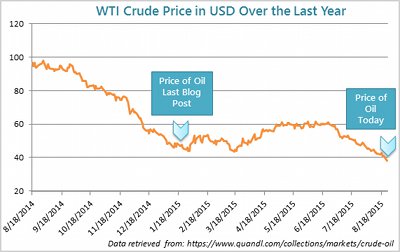

Back in January, I wrote a post about falling oil prices, which were then dipping below $50. While your friendly neighborhood analytic software vendor is not in the business of forecasting commodity prices, we hate to pass up an opportunity to talk about ubiquitous uncertainty, and oil prices are a classic example.

China is the world’s largest oil importer, sucking in over 7 million barrels a day (paywall), and with its stock market and possibly its economy taking a bit of a dive, oil prices have recently fallen below $40 (at least for WTI, Brent is a few bucks higher). (Economic statistics from the government of China are an excellent example of Imperfect Information, but that’s a subject for a different post.)

In the press, the consensus seems to be that current price levels are just too low to persist. However, the same consensus, dialed back a year or so, would have discounted the possibility of being where we are now. We know that in the long run nobody will invest in capacity if they can’t get a decent return on their capex, but in the short run, assets in the ground will continue to produce, in all but the most extraordinary circumstances. In the short and even medium term, the market can and often does overshoot the smooth line of the fundamental fully loaded marginal cost.

Pivoting for a moment to management science, one of the great challenges in probabilistic forecasting is overconfidence: people, even well informed experts, tend to underestimate the amount of uncertainty when talking about the future. If asked for a range, say an 80% confidence interval, they provide something more like a 40% confidence interval. There are a number of interviewing techniques decision consultants can use to try to “stretch” the thinking of an expert or a group to reduce overconfidence, and one of the more colorful ones is called backcasting. In backcasting, the facilitator thinks up a provocative future headline (e.g., “March 2017: Google declares bankruptcy”), and the group must tell a “backcasting” story leading from the present to the outcome described in that headline. Often a seemingly outrageous headline can be justified with a surprisingly believable story. If you think about it, most of the events you read about in the newspapers were unlikely, until they happened.

So, now that we know what backcasting is, let’s tell a story for $20 oil.

- Post-sanctions Iran, already a top-10 exporter, ramps up with a vengeance, half a million bbl/day above current estimates.

- Growing extremism in Saudi Arabia, partly funded by Iran, forces the ruling monarchy to throw more money at its restless subjects. Dwindling foreign exchange reserves, and falling prices, force the Kingdom to sell still more oil to balance its budget. Add a couple million bbl/day (a lot, but still less than their spare capacity).

- China’s economy falls sharply into a recession, as the government flails around looking for levers they can pull. Imports fall by 1.5 million bbl/day (still above 2012 levels).

So, without even trying very hard, we’ve added 4 million bbl/day of oversupply into a ~85m bbl/day world oil market already in near glut territory. Oil can be stored to some extent, but current stocks are already high. Even at current price levels, many petrostates are desperate for cash, and will increase exports any way they can, adding downward pressure to prices.

Do I think all this is likely (i.e., more than 50% chance of it happening)? No. But it’s plausible, and it’s not the only story that would lead to much lower oil prices in the short term. If our view of the likelihood of really cheap oil has increased, then knowing what we know about overconfidence bias, that’s probably a step toward more accurate assessments.