In an earlier post I argued that the #1 cause of downward project revisions in portfolio analysis is a phenomenon called “winner’s curse”, whereby the error in estimating project values, together with screening criteria, results in more negative surprises than positive ones. In this post, I’ll talk about the #2 reason (which might be the #1 reason in some portfolios). This reason is more straightforward, it’s about what we mean by success.

Let’s consider a simple model of the value of a potential new drug entering clinical development. (Pharma R&D is the classic example, but this result holds for portfolios in other fields in which there are a series of hurdles and most projects fail, such as new product development, venture capital, etc.) We’ll strip the decision tree bare so it includes only four nodes: success/failure for phases I, II, III and FDA approval. (For a more complete Pharma R&D tree, see this post on Pharma model tornadoes.) If the project fails, we will lose the amount spent up to that point (and clinical trials aren’t cheap), but if the project is successful, we’ll have a drug on the market and will hopefully make some money.

To populate this tree with data, we’ll need the following information:

- The probability of success for the 3 phases plus FDA approval

- The cost of development for each phase

- The commercial value of the project given that it is successful (revenues minus marketing and manufacturing costs)

Who collects that information and makes those assessments? Well, for the first two items, those are questions that would be answered by people in the R&D part of organization. The clinical development project team is closest to the action and has the most information, and subject to some outside review and comparison against benchmarks, they’re the ones who can make the best assessments. The last item would be assessed by people in the commercial part of the organization. They’re the ones marketing drugs that are already on the market, presumably in the same therapeutic area, so they know what the medical needs are and how physicians are likely to react to the new drug.

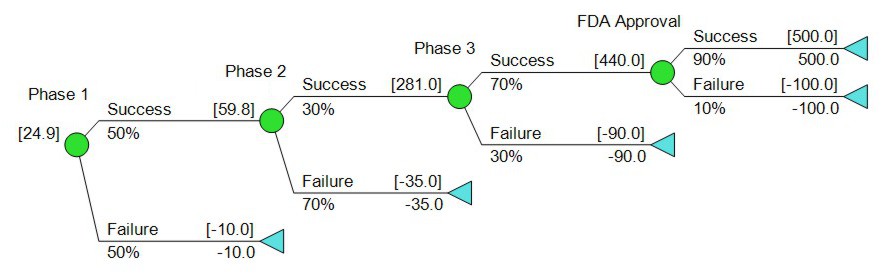

Let’s put some numbers on the tree. The teams have done their technical and commercial assessments, and given us this:

When we run the numbers, the tree above gives us an expected value of about $25M. So far so good? This approach is reasonable enough, and done carefully it can produce an answer that’s in the right ballpark, but it does leave one huge pitfall, which is confusion about the definition of success. To the R&D people, success means the FDA eventually approves the drug, in some form and for some disease, whatever the particulars. The commercial people, asked to estimate the value of the drug if successful, need some definition of what it is that’s being sold.

The product profile of a drug is a composite of what kind of product we have: is it a convenient drug with no side effects recommended for everyone, or does it have some issues, maybe the need for frequent dosing or the chance of a serious side effect. For most drugs early in clinical development there are many possibilities, and to have a reference point for planning, most organizations will define a target product profile. The target product profile is the goal. It may not be the absolute best possible case, but it’s usually a very good one. However, there are a lot of reasons a drug can be something of a dud, without failing outright. It might have a side effect so severe it warrants a black box, the formal way the authorities warn doctors that this is scary stuff. It might be indicated only for a rare disease, or only for use as a second line therapy after other drugs have failed. Inhalable insulin, once the holy grail of diabetes drugs, provides some noteworthy examples of big duds, Exhubera and Afrezza.

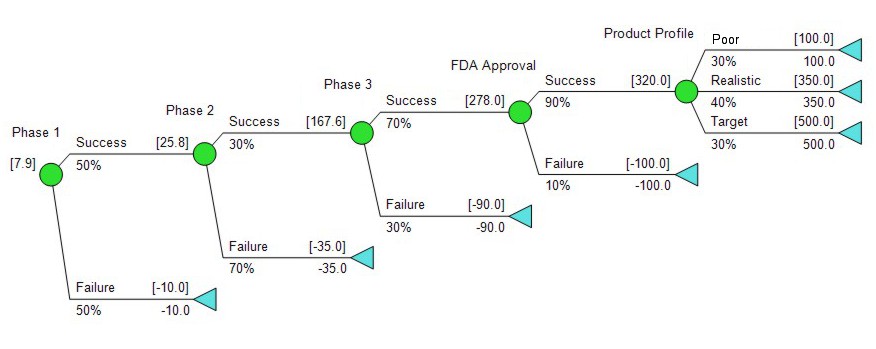

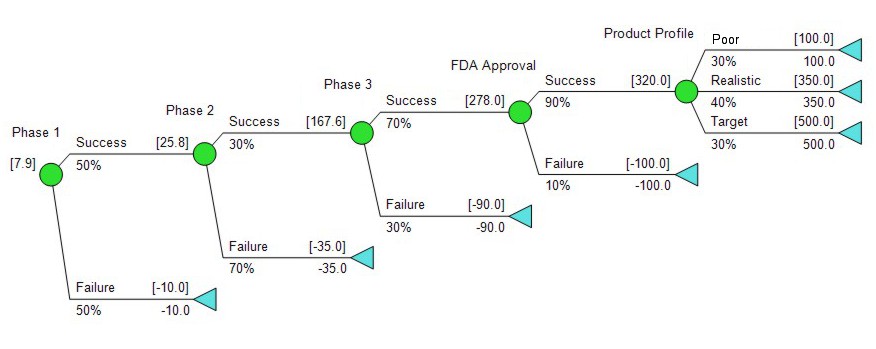

How much difference does it make if the technical assessments are based on any product and the commercial assessments are based on a target product? In practice, it makes a huge difference. In our example, if we consider the target product profile to be the highest of three scenarios, we might end up with something like this:

This new, more realistic tree has an expected value of $8M, roughly a third as much as the naive one above, all because we’ve been less glib with the product profile. These example numbers are made up, but they’re broadly consistent with what happens in the real world.

You may be thinking, do people really get this wrong in big, smart, successful life science companies with a lot at stake? The answer is a qualified yes. They usually get it right late in development, when the potential revenue is only several years away and it’s on the radar of senior management and Wall Street analysts. But early in development, when the project is likely to fail (most do) and is a decade from fruition in any event, it’s common to take the shortcut of considering only a single product profile, and not always one that is realistic and well defined. It’s hard work to develop product profile scenarios and assess their probabilities, and for an early stage project it may not seem worth it.

Putting it all together, a systematic bias towards optimism at the early end of the pipeline, gradually disappearing as projects get closer to market, and you see why product profile befuddlement can lead to frequent downward revisions of project value across the portfolio.